Flores

Tura Jaji

For generations, Tura Jaji, a culture among Ende Lio community, consists of an oath containing agreements made and always upheld for those who make the oath, it means “a layered promises between Human, Nature, and God.” It is a sacred promise that is passed down by the ancestor and is respected by locals.

The role of Tura Jaji culture is to increase solidarity, managing social conflicts, maintaining culture and creating social integration. As recent developments threaten to erode the sanctity of their community lands, the cultivation of coffee emerges as an act of resistance, a means to fortify their cultural boundaries against external pressures.

In their villages, amidst the breathtaking vistas, the cultivation of coffee transcends mere economic endeavor, it embodies a commitment

to safeguard their lands. By creating and exploring new coffee origins like Flores, Adena Coffee aspires to preserve more heritage and uphold this symbiotic relationship between land, people, and their culture.

Image Caption

Image Caption

“Together with Adena, I started to realize the dream of building education and economy in my village by continuing to preserve the Lio culture.

Through coffee, the village’s economy is growing and thanks to the transfer of knowledge from the Adena team, now we understand how to produce coffee with good quality.” —Ferdy Rega

Adena started working as Processor in Flores Kelimutu back in 2017. Started from Desa Sokoria, then slowly reached out the surrounding villages. As per today, Adena is working with five villages and involving 600 farmers households. We started our project from Desa Sokoria, which is Ferdy’s birthplace. Sokoria has a huge potential for farming, especially coffee commodity. While we were starting our coffee processing in Sokoria, at the same time Geothermal Power Plant project was set up nearby, and many team members were involved in the construction project.

Adena encourage the local community to register themselves as a Co-op to broaden their opportunities.The Co-op existence now has reached out the surrounding communities such as : Desa Toba, Desa Tenda Monggi, Desa Demulaka, and Desa Roga. Actively involved in social and empowerment activities, the Co-op is now associated with the Kelimutu National Park and also with Ende government. Adena has developed four processing centers : Sokoria, Tenda Monggi, Demulaka, and Toba just recently.

Adena constantly seek for better quality and efficiency, and also better impact for nature and local communities. We believe shadely-grown coffee elevates its quality and ecosystem sustainability. Shade trees grown here are Calliandra sp., Musa sp. (local bananas), Falcataria sp., avocado, local citrus, pomelo, and the endemic shading trees are ‘Waek’, ‘Natu’, and ‘Worok’.

We are always involved in the local cultural activities and delighted to be included in every ceremony, to look closer at the beauty of it. Inline with our vision which is to bring out the dignity of local culture, knowledge, agriculture, and local resource.

Ferdy was working as an elementary school teacher, before coming home to developing the Flores Tura Jaji coffee. Thus, he initiated an educational projects for kids from the farmer households : KOPINTAR, funded by the Flores Tura Jaji Coffee project. Its current programs include: English Conversation Practice, Study Tour, and Educational Savings.

Desa Toba is our biggest processing center and together we have built :

- Green houses / drying houses

- Raised beds

- Washing stations

- Wet Mill (Pulpers)

- Dry Mill (Dry Huller)

- Wet Hull station

- Warehouses

Adena process variety of products:

- Full Washed

- Honey Process

- Natural Process

- Fine Robusta Natural

Cultivar :

- Typica

- Lini-S

- Catimor

- Kolombia / Bourbon

Our Partner in Origin

Ferdi Rega

Origin Partner - Flores

Flores

Wae Rebo

COFFEE, ECOLOGY, AND LOCAL WISDOM

Waerebo, an ancient village surrounded by mountain ranges and tropical forests in Flores, at 1,100 meters above sea level. Waerebo has now reached its 18th generation, with one generation counted as 60 years, making the village approximately 1,080 years old.

“Neka hemong kuni agu kalo” is an expression deeply rooted in Wae Rebo, referring to Wae Rebo as the birthplace, the ancestral land, the land of origin that must never be forgotten.

This village is also famous for its high-quality Arabica coffee, grown on mountain slopes with organic methods as both source of livelihood and ritual drink. Coffee here is not merely an agricultural commodity; it is embedded within a socio-ecological system shaped by ancestral knowledge, spatial order, and intergenerational responsibility. Coffee cultivation here reflects what anthropologists describe as a “biocultural landscape”, a landscape where ecological processes and cultural practices co-evolve (Berkes, 2012).

Arabica coffee in Wae Rebo is grown within forest-based agroforestry systems, often intercropped with shade trees that protect soil moisture, regulate microclimates, and preserve biodiversity. Such systems align with findings in agroecology research, which show that shaded coffee farms support higher species richness and ecological resilience compared to monoculture systems (Perfecto et al., 2005; Jose, 2009). In Wae Rebo, shade is not introduced as an “innovation,” but as a continuation of customary land ethics that prohibit excessive clearing and emphasize balance between use and protection.

Local wisdom in Wae Rebo recognizes land as a living entity rather than an extractive resource. This worldview resonates with what political ecologists term relational land stewardship, where humans are considered caretakers rather than owners of nature (Escobar, 2018). Coffee gardens are maintained with restraint, production is limited by ecological boundaries and ritual calendars, reinforcing the idea that abundance must not come at the cost of imbalance. The Wae Rebo community protects its water sources by preserving forest buffers around springs, maintaining natural filtration that sustains both households and coffee farms.

Uma bate duat, the cultivated gardens and coffee fields, represent the space for labor and sustenance, where working with the land maintains both livelihood and reciprocity with nature. Mbaru bate ka’eng refers to the dwelling houses, where everyday life unfolds and familial ties are nurtured. Wae bate teku, the protected water sources, symbolize life itself, ensuring that the village can persist across generations. Finally, Natas bate labar, the open communal yard at the village’s center, is where children play, elders gather, ceremonies are held, and social bonds are renewed. Together, these four realms reflect a relational worldview: that a community survives not only through shelter and work, but through shared resources, common spaces, and the stewardship of water and land as ancestral responsibilities.

Coffee also plays a central role in social cohesion and hospitality. The act of serving coffee to guests is a ritualized gesture of welcome, positioning coffee as a mediator between the village and the outside world. This practice aligns with anthropological observations that food and drink often function as “social glue,” reinforcing trust, reciprocity, and identity within and beyond the community (Mintz & Du Bois, 2002).

However, as global market forces and tourism reshape livelihood options, the continuity of coffee knowledge faces new pressures. Younger generations increasingly pursue tourism-related work, which offers faster economic returns than farming. Scholars of rural development note that such shifts often lead to a knowledge gap, where traditional ecological practices risk being lost despite their proven sustainability (Pretty, 2011). In Wae Rebo, this challenge is not rooted in a lack of ecological awareness, but in insufficient economic incentives to sustain long-term agricultural stewardship.

Positioning Wae Rebo coffee as a limited, premium origin becomes a strategic intervention rather than a branding exercise. From an economic anthropology perspective, value here is redefined, not by volume, but by cultural meaning, environmental care, and traceability (Appadurai, 1986). Premiumization, when paired with direct reinvestment into farmer training and regenerative practices, enables the community to translate ancestral wisdom into contemporary economic relevance.

Thus, coffee in Wae Rebo exists at the intersection of heritage conservation, ecological resilience, and livelihood regeneration. It is a living practice that sustains soil, culture, and community, demonstrating that sustainability is most durable when it emerges from local knowledge systems rather than external prescriptions.

TRACEABILITY, STEWARDSHIP, AND MARKET MEDIATION BY ADENA COFFEE

Within this socio-ecological context, the role of market intermediaries becomes critical in determining whether local knowledge systems are sustained or eroded. In Wae Rebo, Adena’s position as the sole buyer functions not as a monopolistic mechanism, but as a governance arrangement that enables traceability, accountability, and coordinated reinvestment across the value chain.

Scholars of value-chain governance argue that fragmented markets often undermine sustainability outcomes, as price volatility and multiple intermediaries dilute responsibility and weaken incentives for long-term stewardship (Gereffi et al., 2005). In contrast, consolidated buying structures, when paired with transparent practices, can reduce transaction complexity and allow for direct alignment between production practices, quality standards, and reinvestment mechanisms.

As the sole buyer, Adena is able to maintain full traceability from farm plots to processing and export. This traceability does not merely serve compliance or market transparency; it enables feedback loops between ecological practices and economic outcomes. Traceability systems have been shown to support sustainability when they are used not only for verification, but also for learning, adaptation, and collective decision-making (Mol, 2015).

Crucially, sole-buyer stewardship allows Adena to internalize responsibilities that are often externalized in conventional commodity systems. Pricing structures, quality differentiation, and volume decisions can be calibrated to reflect ecological limits and labor realities, rather than maximizing short-term extraction. This aligns with emerging frameworks in ethical supply chain management, which emphasize responsibility proportional to control (Locke, 2013).

In the case of Wae Rebo, traceability under a single-buyer model supports the intentional positioning of coffee as a limited-supply origin, reinforcing production boundaries that are consistent with customary land ethics. The economic premium generated through this positioning can then be reinvested into training, regenerative practices, and intergenerational knowledge transfer, closing the loop between market participation and cultural continuity.

From an academic perspective, Adena’s role can thus be understood as that of a market steward, mediating between global demand and local socio-ecological systems. Rather than replacing indigenous governance, this role operates alongside it, translating local values of restraint, balance, and care into legible forms within international coffee markets.

This arrangement illustrates a broader insight from sustainability scholarship: that durable environmental outcomes are most likely when market mechanisms reinforce, rather than override, local institutions and knowledge systems (Ostrom, 2009). In Wae Rebo, traceability and sole-buyer stewardship become tools not of control, but of continuity, ensuring that coffee remains a viable livelihood embedded within its ancestral landscape.

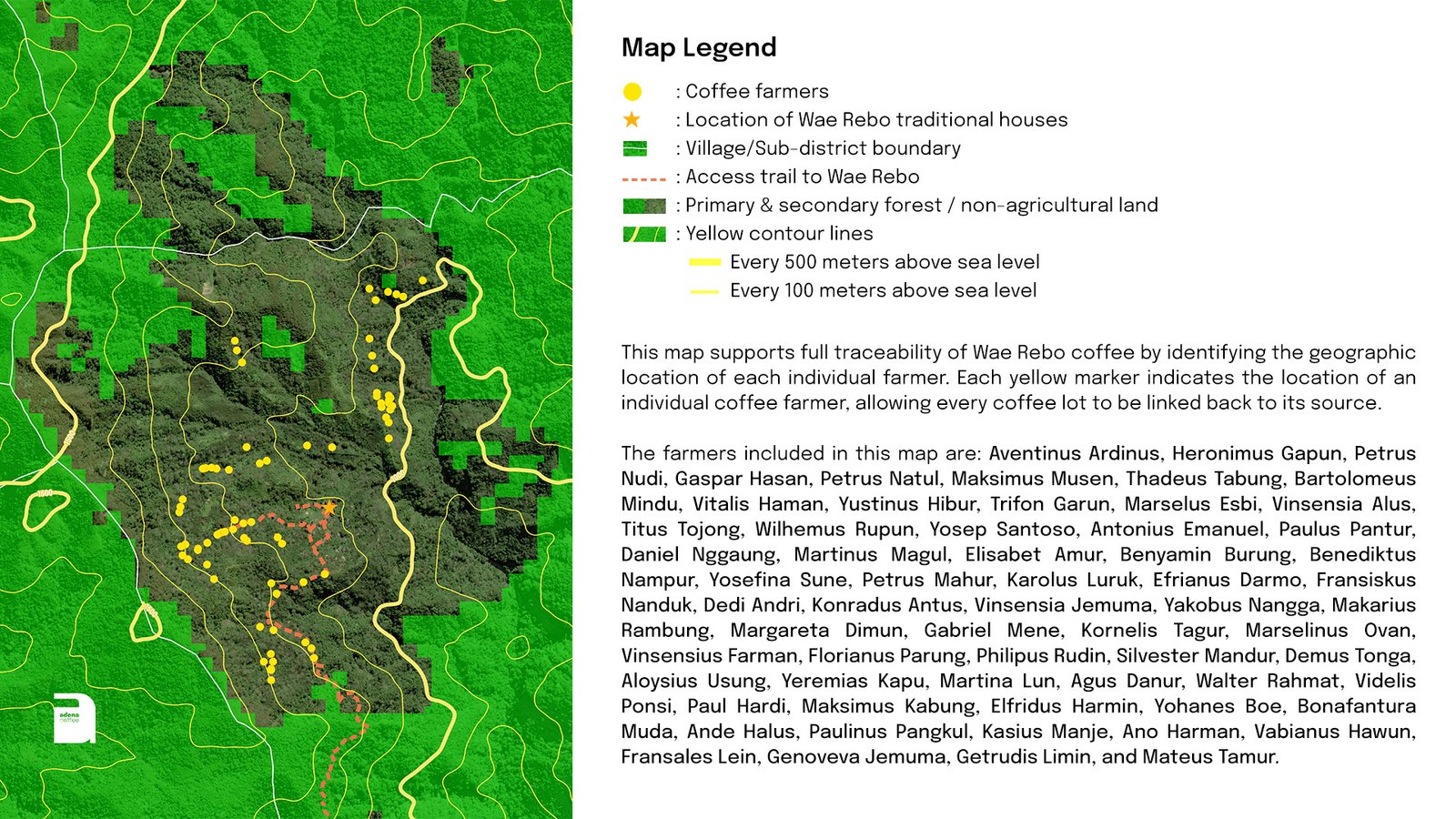

This traceability map is part of our first complete report from Wae Rebo, an indigenous village where sustainability has always been a way of life. As forests are protected and land is cared for across generations, today’s challenge lies in regeneration, with fewer young people choosing to farm as tourism grows. This is why Wae Rebo coffee is naturally limited, shaped by cultural and ecological boundaries that must be respected. Working directly with the community as the sole buyer, Adena Coffee ensures full transparency from farm to cup while returning value to the people. By positioning Wae Rebo as a premium, limited origin, we support regenerative practices, fair compensation, and the quiet continuity of a living legacy.

Sumatera

Kenawat is Adena Coffee’s first origin. Formerly serving as a focal point for a separatist movement, its topography once bore witness to the fervent calls for autonomy. This village has undergone a metamorphosis and now stands as a burgeoning epicenter of coffee production. Through the cultivation of premium coffee beans, this locale not only contributes to the regional coffee industry but also symbolizes a poignant narrative of reconciliation and socio-economic revitalization.